By Zach Nickels, Elizabeth S. Dipchand

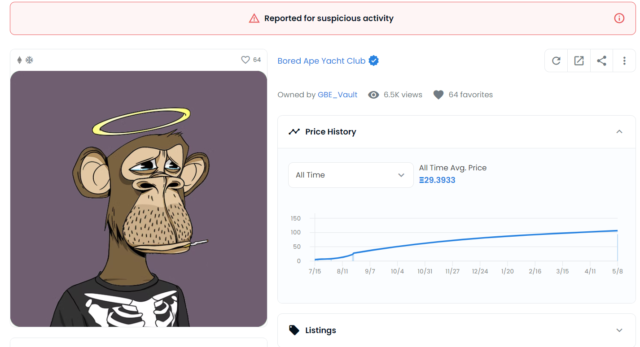

Image of Bored Ape #8398 AKA “Fred Simian” (image via OpenSea)

The recent theft of four of actor Seth Green’s (“Green”) NFT’s has stoked the fire for further debate about the intersection of personal property rights, licenses, and intellectual property rights in the context of NFTs. Beyond Green’s obvious financial loss, the situation is complicated by the fact that he has spent several months developing an animated TV series featuring as the main character one of his stolen NFTs, Bored Ape #8398 AKA “Fred Simian” (“Bored Ape”).

Now, Green has a serious problem on his hands: he did not actually own the copyright in the NFT’s artwork as the (former?) Bored Ape owner, he only had a licence for its commercial use. As such, his ability to use Bored Ape in the show and his avenues for legal recourse are unclear.

The Facts

On May 8th, 2022 four of Green’s NFTs were stolen in a phishing scam, where the Bored Ape was eventually sold to a pseudonymous collector identified as “DarkWing84”. The Bored Ape was (unwittingly?) purchased by DarkWing84 for over $200,000 and transferred to a collection identified as “GBE_Vault” where it currently remains, and has since been frozen by the NFT marketplace OpenSea.

Although Green tweeted over the past weekend that he would like to get in touch with the DarkWing84 to “fix” the situation, the two have yet to make contact. In a recent interview with DarkWing84, she said that although he was interested in talking with Green, he had “no plans” yet for the Stolen Ape. Green has since tweeted that he would “rather meet DarkWing84 to make a deal, vs in court [sic]”. If this situation does escalate to litigation, it would provide a great opportunity to clarify how courts characterize NFTs and how NFTs square with intellectual property laws.

The Fine Print

At front and center in this conundrum is the nature of the rights acquired by purchasers of NFTs, here the Bored Ape NFT purchasers (“Owners”). Rights conferred by copyright ownership must be distinguished from rights arising from copyright licences which commonly grant permission to use under certain conditions. Copyrights provide an owner the exclusive right to produce, reproduce, sell, publish, perform or licence a work. In contrast, copyright licence only allows a licensee to do the specific thing(s) that the copyright owner allows them to do. In this instance, Green did not own the copyright to the Bored Ape – he only had a commercial licence to use the “Fred” as long as he owned the NFT.

Looking at Bored Ape Yacht Club’s (“BAYC”) rather sparse and somewhat contradictory Terms and Conditions (“Terms”), Owners own “the underlying Bored Ape, the Art, completely”. However, this section appears to only refer to personal property rights in the token and Art, as the Terms’ Commercial Use clause clarifies that Owners merely have an “unlimited, worldwide license to use…” the purchased Art for commercial purposes, as opposed to full copyrights in the Art. In other words, although the Terms say Owners own the Bored Ape and the Art “completely”, they actually do not own the copyright in the Art and only have a licence to use the Art commercially. In Canada, this is a critical practical reality given that any assignment of copyright ownership needs to be in writing and signed by the author. Although it is not explicitly stated, this commercial licence right seems to transfer with the NFT itself based on whoever owns it.

Since Green’s commercial use rights appear to be contingent upon his ownership of the Bored Ape and the licence seems to transfer with the token itself, his ability to feature the Bored Ape in his TV series with impunity seems to be in legal purgatory until this dispute is resolved. Unfortunately for Green, BAYC is unable to intervene in the matter, as their Terms explicitly state that “[u]sers are entirely responsible for the safety and management of their own private Ethereum wallets…” and that “at no point [will BAYC] seize, freeze or otherwise modify ownership of any Bored Ape”.

Apes As A Barrel of Monkeys vs Negotiable Instruments – Nemo Dat or Not?

While its not entirely clear how a court may respond to a request for relief from Green – presumably seeking to re-establish his ownership of the Bored Ape and commercial licence to use it in his TV series –it has not derailed consideration and debate from a few camps online.[1]

One avenue open to common law courts is the old common law rule of nemo dat quod non habet, namely, “no one can give better title than he himself has” (“Nemo Dat Rule”). In other words, you cannot give another person legal rights that you do not have yourself. Since the thief did not have legal rights to the Bored Ape at the time of the transfer, Darkwing84 could not acquire any legal rights in the Bored Ape at the time of its purported sale,[2] including the licence for commercial use of the NFT’s Art. Under this principle the Bored Ape (and all associated rights he held before the theft, including the commercial licence) could revert to Green the same way stolen tangible personal property would, restoring his ability to use “Fred” in his TV series. This approach would focus on maintaining Green’s personal property rights in the Bored Ape, despite the malfeasance of the thief and the DarkWing84’s lack of notice.

However, it would also be open to the court to apply one of the exceptions to the Nemo Dat Rule by considering the Bored Ape as a negotiable instrument instead of personal property. Negotiable instruments can be described as documents that guarantee the payment of a specific amount of money to a specific person, such as a bearer stock certificate. Negotiable instruments are essentially “tokens” that represent rights in something else – a characteristic that Bored Ape NFTs arguably share to some extent. From a policy perspective, tokenization serves a commercial purpose by allowing tangible items of trivial worth (i.e. pieces of paper) to represent monetary value.[3] NFTs could also arguably be construed as serving a similar commercial efficacy purpose.

This is an important point because when someone purchases a negotiable instrument for value without notice, the Nemo Dat Rules does not apply.[4] Thus, if DarkWing84 had no notice of the circumstances underlying the transaction and a court were to characterize the Bored Ape as a negotiable instrument instead of personal property or chattel, it is open for her to argue that Green may not be able to recover the NFT and potentially expose himself to liability for copyright infringement by using “Fred” in the TV series.

If Green had owned the copyright in the Art from the outset, recovering the NFT and restoring his status as an Owner to re-assume the commercial use licence would be a moot point. Ownership of the personal property that contains or incorporates a copyright protected work is not necessary for an author to maintain their ownership of the copyright in the work itself. For example, if Green was the author of an original work of (let’s say a portrait of “Fred”) instead of a merely a prior Owner of the Bored Ape NFT, it wouldn’t matter if the painting had been stolen or sold to a third-party. He would still own copyright in the work and enjoy the right to exploit it.

Don’t Wait Until You’ve Got A Monkey On Your Back – Understand Your Rights, Identify and Protect Your Intellectual Property

While we will have to wait to see how this situation unfolds, it serves as a reminder of the importance of understanding the intersecting legal rights associated with ownership of NFTs. Regardless of whether you are looking to mint NFTs, purchase them, or create derivative works based on NFT artwork, it is imperative you understand the scope and extent of your rights with respect to the NFT and its how they interact with other legal rights.

[1] Twitter user @gonbegood is one such commentator who has discussed what could happen to Bored Ape NFT Owners’ rights if their NFTs are stolen, depending on whether courts characterize the NFT as property/chattel versus negotiable instruments.

[2] Historically, one of the exceptions to the Nemo Dat Rule was the Sale In a Market Overt” exception. This exception held that where goods were sold in a market overt (a public and legally constituted market) according to the usage of the market, the Nemo Dat Rule did not apply. The idea was that in medieval times, if the victim did not bother to check their local market for their stolen goods, they were not being sufficiently diligent. Although the application of this exception has been abolished in Ontario by section 23 of the Sale of Goods Act, R.S.O. 1990, c. S.1., one can wonder whether OpenSea could be considered a market overt otherwise? Probably not.

[3] For an in-depth discussion of tokens and property law (which actually concludes that traditional property concepts do NOT support the idea that NFTs are true tokens), see https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3928901 by Juliet M. Moringiello and Christopher K. Odinet.

[4] For example, see UCC SS 3-306; Bills of Exchange Act s. 55(1)(b).